Abstract

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis is a viral infection of the retina caused by the cytomegalovirus, a member of the herpesvirus family.

It primarily affects individuals with weakened immune systems, such as those with advanced HIV/AIDS, organ transplant recipients, or individuals undergoing immunosuppressive therapy.

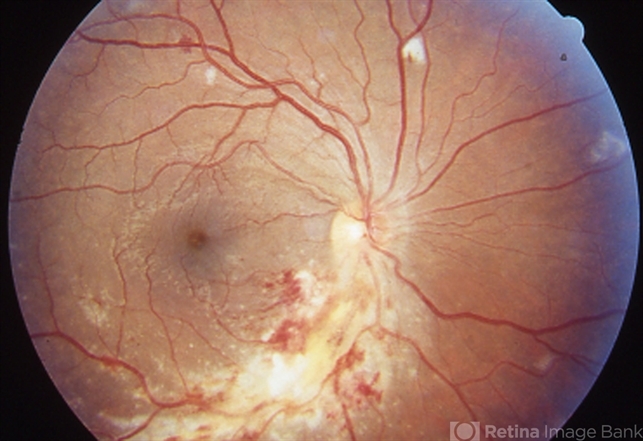

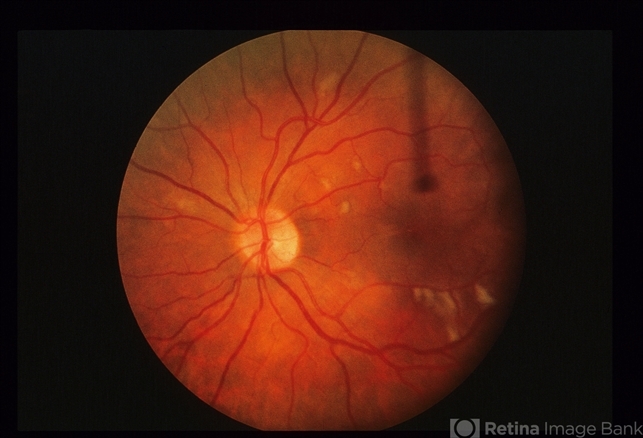

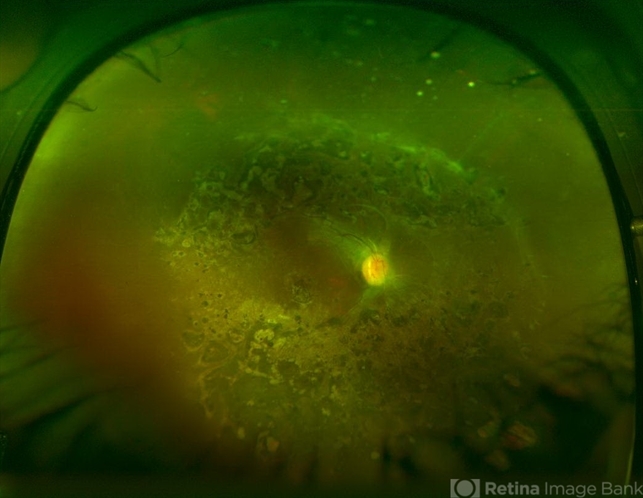

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Retinitis can lead to progressive damage to the retina, causing characteristic features such as retinal necrosis, hemorrhage, and detachment, ultimately resulting in vision loss if left untreated.

It is considered an opportunistic infection and requires prompt diagnosis and management to prevent irreversible vision impairment.

Treatment typically involves antiviral medications administered locally (intravitreal injections) and systemically (oral or intravenous), along with optimization of the patient’s underlying immunocompromised condition, such as through antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected individuals.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Retinitis Management

Management is largely medically based with intravenous (IV), oral, and intravitreal anti-viral medications. Topical corticosteroids can be used to treat anterior chamber inflammation. Management also hinges on HAART in HIV-positive patients.

Patients should be started on high-dose induction therapy, which is followed by continuous maintenance therapy until CD4 counts increase, HAART is therapeutic, and Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Retinitis shows no progression.

General treatment:

There are at least 8 options for therapy of Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Retinitis:

- Oral valganciclovir

- Intravenous ganciclovir

- Intravenous foscarnet

- Intravenous Cidofovir

- Intraocular ganciclovir device

- Intravitreal ganciclovir

- Oral leflunomide

- Oral letermovir

Medical therapy:

First-line therapy is generally oral valganciclovir, which is a pro-drug of ganciclovir. The induction dose is 900 mg twice daily for 21 days followed by maintenance of 900 mg daily.

Valganciclovir has increased bioavailability compared to oral ganciclovir and does not require IV administration, making it a favorite for patients and doctors alike.

However, the cost of therapy is high and patient compliance can be a problem, especially in developing countries.

This should be avoided if hemoglobin is <8gm%, the absolute neutrophil count is less than 500 cells/µL, and the platelet count is less than 25,000/µL.

IV ganciclovir is given at 5 mg/kg twice daily for two to three weeks as induction therapy then followed by daily 5 mg/kg infusions. This can be quite cumbersome for patients.

Foscarnet is given at 90 mg/kg twice daily for two weeks followed by maintenance therapy of 90-120 mg/kg daily through IV infusion.

Cidofovir has a longer half-life and can be administered weekly during induction followed by bi-weekly maintenance therapy.

The dose is 5 mg/kg weekly during induction, and 5 mg/kg every other week during maintenance. Cidofovir can cause severe nephrotoxicity, so is typically given with saline hydration and high-dose probenecid therapy.

Oral ganciclovir can be considered for maintenance therapy but regression and involvement of fellow eye is more frequent.

Intravitreal ganciclovir, foscarnet, or cidofovir can be considered for short-term management.

Other options for therapy are oral leflunomide and oral letermovir. These therapies are used much less often but have been effective in patients who are experiencing side effects of other medications.

Maribavir, a director UL97 inhibitor, has also demonstrated efficacy in treating resistant strands which may be a forthcoming viable systemic treatment option.

In patients with immediately sight-threatening lesions (lesions close to the macula or optic nerve head), intravitreal injection of ganciclovir (2mg/injection) or foscarnet (2.4 mg or 1.2 mg /injection) or fomvirsen 330 micrograms, or cidofovir 20micrograms with concurrent systemic therapy can be done.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Retinitis can become drug-resistant the longer the duration of treatment lasts. Resistance can be caused by immunosuppression after organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplants, where specifically ganciclovir and valganciclovir resistance have been reported.

Medical follow up

Depending on the medication used, complete blood counts, chemistries, and intraocular pressure checks will be needed.

Dilated eye exams should be performed at least weekly initially, then 2 weeks after induction therapy, followed by monthly thereafter while the patient is on anti-CMV treatment.

Fundus photographs can be helpful in detecting early relapse. Patients should be followed in an appropriate HIV clinic with CD4 counts and viral load studies.

Surgery

The only initial surgical management involves intravitreal placement of intraocular ganciclovir devices. They have a relatively low-risk profile and can last 6-8 months.

They afford no protection to the fellow eye, however. In addition, these implants are not readily available.

Surgery can also be performed for complications of retinitis that include rhegmatogenous retinal detachments.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Retinitis surgical follow-up

Look for complications of silicone oil, especially cataracts and glaucoma. Many patients are one-eyed and silicone oil may need to be left for a long duration.

Complications

The most serious complication of therapy for Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Retinitis, besides those listed above due to medications, is immune recovery uveitis (IRU).

As the CD4 counts rise with HAART, it is presumed that reactions to CMV antigens cause anterior or intermediate uveitis.

Cystoid macular edema and epiretinal membranes are also potential complications of IRU. Posterior capsular cataracts, proliferative vitreoretinopathy, and optic nerve neovascularization are possible complications as well.

HAART therapy can also unmask Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Retinitis in a patient without prior CMV disease (unmasking CMV-immune recovery retinitis (IRR)) or can cause worsening of known CMV retinitis (paradoxical CMV-IRR).

CMV retinitis that involves > 25% of the retina can lead to rhegmatogenous retinal detachments from breaks that occur near the thin, necrotic retina.

Peripheral anterior retinal lesions are associated with an increased risk of retinal detachment, due to the anterior adherence of the vitreous base.

Prognosis

The prognosis was almost uniformly fatal prior to the advent of HAART. Now it carries a much better prognosis, but even with HAART and anti-CMV therapy, mortality is still increased after diagnosis of CMV retinitis.

Prognosis for patients with or without HIV infection, corticosteroid immunosuppression, and other risk factors all have similar visual outcomes. The strongest factor associated with poorer visual outcomes for all patients is retinal detachment.

Would you have interest in taking retinal images with your smartphone?

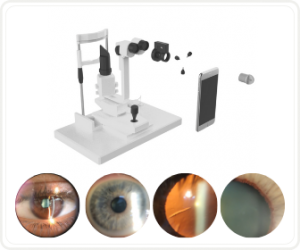

Fundus photography is superior to fundus analysis as it enables intraocular pathologies to be photo-captured and encrypted information to be shared with colleagues and patients.

Recent technologies allow smartphone-based attachments and integrated lens adaptors to transform the smartphone into a portable fundus camera and Retinal imaging by smartphone.

RETINAL IMAGING BY YOUR SMARTPHONE

References

- Jabs, D.A., et al. Cytomegalovirus resistance to ganciclovir and clinical outcomes of patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2003;135:26–34.

- Jabs, D.A., Martin, B.K., Ricks, M.O., Forman, M.S., and Cytomegalovirus Retinitis and Viral Resistance Study Group. Detection of ganciclovir resistance in patients with AIDS and cytomegalovirus retinitis: correlation of geno- typic methods with viral phenotype and clinical outcome. J. Infect. Dis. 2006;193:1728–1737.

- Jabs, D.A., Enger, C., Forman, M., and Dunn, J.P. Incidence of foscarnet resistance and cidofovir resistance in patients treated for cytomegalovirus retinitis. The Cyto- megalovirus Retinitis and Viral Resistance Study Group. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2240–2244.

- Jabs, D.A., Enger, C., Dunn, J.P., and Forman, M. Cyto- megalovirus retinitis and viral resistance: ganciclovir re- sistance. CMV Retinitis and Viral Resistance Study Group. J. Infect. Dis. 1998;177:770–773.

- Myhre, H.-A., et al. Incidence and outcomes of ganciclovir-resistant cytomegalovirus infections in 1244 kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation.2011;92:217– 223.

- Schneider EW, Elner SG, van Kuijk FJ, et al. Chronic Retinal Necrosis: Cytomegalovirus necrotizing retinitis associated with panretinal vasculopathy in non-HIV patients. Retina 2013; 33 (9): 1791-9.

RETINAL IMAGING BY YOUR SMARTPHONE

RETINAL IMAGING BY YOUR SMARTPHONE